Christmas has a dark edge. That is certainly true of Jesus’ birth. Some people honored Jesus after his birth, and others wanted to destroy him. This story is found in Matthew 2:13-23, the text Brian Watson addresses in this sermon, preached on December 27, 2020.

Exile

Prepare to Meet Your God

This sermon was preached by Brian Watson on May 3, 2020.

MP3 recording of the sermon.

PDF of the written sermon (or read below).

Many of us have been spending more time at home than we’re used to spending. Some of us have spent more time at home than we want to spend. A few weeks ago, my wife said she felt like she was “in prison.” Isn’t it strange to think that we don’t feel at home while at home? Shouldn’t home be where we feel best?

Perhaps what we’re longing for is something more than being home. Perhaps we’re longing to be in our real home, the place where we really feel best.

C. S. Lewis addressed this issue in his sermon, “The Weight of Glory.” He said that we have this “desire for our own far-off country,” our real home.[1] What we’re longing for cannot be found in this world. But still we try to find it here and now. We try to something that will satisfy our longings in beauty and pleasures. Some of us may try to find what we’re looking for in the past. If only we could back, then everything would be right. Lewis says, “But this is all a cheat. . . . These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself, they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.”[2]

We all need a people, a place, and a purpose. Without those things, we will never be satisfied. We were made to be God’s people, to dwell with him, and to live for him. What we really need to be satisfied is a right relationship with God. We were made for God. Being with him is our true home. Taking pleasure in praising him is our purpose. As Augustine prayed over sixteen hundred years ago, “You stir men to take pleasure in praising you, because you have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.” [3]

The story of the Bible is a story about leaving home and getting lost in our wanderings. It is a story about God calling us back home. He sends things into our lives to get our attention, to summon us back to himself—if only we would listen and return to him. It is a story about God coming to take us back home. And the end of the Bible is a depiction of that glorious homecoming, when all things will finally be well.

Today, we’re going to focus on the part where God sends things into our lives to call us back to himself. I think that’s appropriate in the age of the coronavirus. I don’t know exactly why this virus exists, but I think it’s possible that God is using this event to get our attention, to remind us of how much we need him.

Today we’re going to look at the book of Amos, from the Old Testament. Amos is one of the so-called “minor prophets.” However, I wouldn’t use that name. Some people refer to the “major prophets,” like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. They use that name because these are some of the longest books in the Bible. And then they refer to the “minor prophets,” the last twelve books of the Bible, which are significantly shorter. But it’s a mistake to think of these books as “minor.” They are very important.

Let’s get a little historical background for this book. It begins with these words:

The words of Amos, who was among the shepherds of Tekoa, which he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah king of Judah and in the days of Jeroboam the son of Joash, king of Israel, two years before the earthquake (Amos 1:1).[4]

Amos was a shepherd who lived in the eighth century B.C. During this time, Israel had divided into two kingdoms. The northern kingdom was called Israel, and during this time Jeroboam II was king (793–753 B.C.). The southern kingdom was called Judah, and during this time Uzziah was king (791–740 B.C.). Both kings reigned for over forty years, which meant that this was a time of unusual stability. It was also “a period of unprecedented prosperity.”[5] Both kingdoms were wealthy. But these kingdoms were surrounded by enemies. In particular, the northern kingdom was threatened by the Assyrian empire, which was becoming the world’s superpower.

The book begins with a word of judgment against the nations around Israel and Judah. This is what the second verse of the book says:

And he said:

“The Lord roars from Zion

and utters his voice from Jerusalem;

the pastures of the shepherds mourn,

and the top of Carmel withers” (Amos 1:2).

Amos is sharing a word of judgment against the nations, a word from God, whose voice “roars” from Jerusalem.

First, there is a warning against Syria, represented by their capital city of Damascus (Amos 1:3–5). This was the country north of Israel. Then, there is a warning against the Philistines who lived to the west (Amos 1:6–8). There is also a word of judgment against Tyre, also to the west (Amos 1:9–10). Then, God promises to punish nations to the east: Edom (Amos 1:11–12), Ammon, (Amos 1:13–15), and Moab (Amos 2:1–3).

Why was God going to punish these nations? The Philistines helped Edom by exiling Israelites there (Amos 1:6). The Edomites fought against Israel (Amos 1:11). And the Ammonites did, too. In fact, Amos says “they have ripped open pregnant women” (Amos 1:13). That’s how brutal war can be.

Now, if you lived in Amos’s day, and you lived in Judah and Israel, you would be happy to hear that God’s judgment was coming against these nations. You would think, “Finally, God is doing something to punish these people!” It would be like a Christian who is a Republican hearing that God is going to punish Democrats. God was finally going to punish all the enemies that surrounded Israel.

But then Amos delivers some shocking news. God is going to punish Judah (Amos 2:4–5) and Israel (Amos 2:6–15). Why? Look at Amos 2:4–5:

4 Thus says the Lord:

“For three transgressions of Judah,

and for four, I will not revoke the punishment,

because they have rejected the law of the Lord,

and have not kept his statutes,

but their lies have led them astray,

those after which their fathers walked.

5 So I will send a fire upon Judah,

and it shall devour the strongholds of Jerusalem.”

Judah rejected God’s word, his law. They didn’t keep his commandments.

Then, look at Amos 2:6–8:

6 Thus says the Lord:

“For three transgressions of Israel,

and for four, I will not revoke the punishment,

because they sell the righteous for silver,

and the needy for a pair of sandals—

7 those who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth

and turn aside the way of the afflicted;

a man and his father go in to the same girl,

so that my holy name is profaned;|

8 they lay themselves down beside every altar

on garments taken in pledge,

and in the house of their God they drink

the wine of those who have been fined.

The rich and powerful in Israel bought and sold people. They “trampled the poor.” There was also sexual immorality. Father and son had sex with the same woman. This might have been connected to pagan worship practices. Strange as it may seem, sex was part of the worship in some religions. And the people committed idolatry, which is spiritual adultery. God was supposed to be their only object of worship, but they cheated on him. They worshiped at all kinds of altars built to worship foreign gods.

These are specific charges against a specific people at a specific time and place, but these are some of the major sins in the Bible: using and oppressing people, usually through some kind of economic means; committing sexual immorality; and worship false gods. In fact, you could say that misusing money means that your god is money. Having sex outside of the only proper context for sex—marriage between a man and a woman—means that sex is your god. When anything other than the true God becomes the most important thing in our life, the thing that causes us to love, trust, and obey it, that is our god. That is what we’re worshiping. But we were made for God. And God has every right to punish us when we’re destroying ourselves by failing to live according to his design.

Failing to love God and live for him is also a failure to acknowledge what he’s done for us. God says that he brought Israel out of slavery in Egypt and sustained them until he led them to their own land (Amos 2:10). For all of us, he has given us life and sustains our lives. He is our Maker, the one who sustains every breath and heartbeat, every second that we live. Yet we run away from him.

In chapter 3, we read this:

1 Hear this word that the Lord has spoken against you, O people of Israel, against the whole family that I brought up out of the land of Egypt:

2 “You only have I known

of all the families of the earth;|

therefore I will punish you

for all your iniquities (Amos 3:1–2).

God reminds Israel that he rescued them from slavery in Egypt. And he says that of all the people on the earth, they alone were the ones he “knew.” Now, God is omniscient. He knows everything. He knows everything about us. What this means is that the Israelites were the only ones he made a covenant with. He revealed himself to them. He gave them promises that were tied to his commandments. If they would trust him and live life on his terms, they would live. But they didn’t.

So, God says, because you were my special people and turned away from me, I will punish you. The reason why they are going to be punished is because they should have known better. God had been exceedingly kind to them, and they didn’t appreciate him.

So, God warns them of punishment, punishment that will come through their enemies. He wants them to know that when enemies defeat their cities, it is because he has brought that about. In Amos 3:6, God says,

Is a trumpet blown in a city,

and the people are not afraid?

Does disaster come to a city,

unless the Lord has done it?

Nothing happens unless God has somehow planned it, or even caused it, to occur. That was true of the judgment that would come upon Israel.

But God doesn’t punish because he is unloving. He punishes in order to correct us. He was sending disaster upon Israel to get their attention.

Let’s look at Amos 4:6–13:

6 “I gave you cleanness of teeth in all your cities,

and lack of bread in all your places,

yet you did not return to me,”

declares the Lord.

7 “I also withheld the rain from you

when there were yet three months to the harvest;

I would send rain on one city,

and send no rain on another city;

one field would have rain,

and the field on which it did not rain would wither;

8 so two or three cities would wander to another city

to drink water, and would not be satisfied;

yet you did not return to me,”

declares the Lord.

9 “I struck you with blight and mildew;

your many gardens and your vineyards,

your fig trees and your olive trees the locust devoured;

yet you did not return to me,”

declares the Lord.

10 “I sent among you a pestilence after the manner of Egypt;

I killed your young men with the sword,

and carried away your horses,

and I made the stench of your camp go up into your nostrils;

yet you did not return to me,”

declares the Lord.

11 “I overthrew some of you,

as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah,

and you were as a brand plucked out of the burning;

yet you did not return to me,”

declares the Lord.

12 “Therefore thus I will do to you, O Israel;

because I will do this to you,

prepare to meet your God, O Israel!”

13 For behold, he who forms the mountains and creates the wind,

and declares to man what is his thought,

who makes the morning darkness,

and treads on the heights of the earth—

the Lord, the God of hosts, is his name!

God gave his people famine, bad crops, pestilence, and military defeat—“yet you did not return to me.” That is such as sad refrain. God caused these things to fall upon Israel so that they would return to him, but they didn’t.

I want us to see that God has the power to control all these events. He controls the weather. He causes rain to fall, and he also causes drought. He can direct kings and armies. He uses these things to bring people back to himself.

Now, you may think, “Oh, that’s just the Old Testament. God in the New Testament wouldn’t do such a thing.” But look at Luke 13:1–5:

1 There were some present at that very time who told him [Jesus] about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. 2 And he answered them, “Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? 3 No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. 4 Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem? 5 No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

People tell Jesus that Pontius Pilate has slaughtered some Jews. That’s a form of moral evil, the kind of evil that people do to each other. Jesus asks if this happened because these Jews were worse sinners. The answer is “no.” And he says something like that will happen to everyone who doesn’t repent, who doesn’t turn to God. Then Jesus mentions how eighteen people died when a tower fell. We don’t know why the tower fell. Maybe it fell because it was poorly made. Perhaps the people who made it made it on the cheap, or they didn’t calculate how strong the tower needed to be. Perhaps it was a minor earthquake that caused the tower to fall. It could have been a form of natural evil, the bad things that happen in nature. Again, he says that the people who died that way weren’t worse sinners. But everyone who fails to repent, to turn back to God, will experience something similar.

In short, every time that some evil occurs, it is a reminder to turn back to God. The reason why these evils occur is that humans turned away from God from the very beginning. God made us to love, trust, and obey him and we don’t do that. We want to be our own gods and goddesses. So, God uses evils to punish us, to get our attention, to cause us to turn back to him.

This reminds me of some of the words of C. S. Lewis in The Problem of Pain. First, he addresses our problem with God. Because of our evil nature, we don’t really want to know God as he truly is. He writes,

What would really satisfy us would be a God who said of anything we happened to like doing, ‘What does it matter so long as they are contented?’ We want, in fact, not so much a Father in Heaven as a grandfather in heaven—a senile benevolence who, as they said, ‘liked to see young people enjoying themselves,’ and whose plan for the universe was simply that it might be truly said at the end of each day, ‘a good time was had by all.’[6]

Then, Lewis says that God isn’t that way. God is love, and real love doesn’t coddle. Real love isn’t afraid to let someone suffer, if that is necessary. If your child needs a painful shot to be immunized, you don’t withhold that treatment because she doesn’t like needles. Lewis writes, “Love, in its own nature, demands the perfecting of the beloved; . . . the mere ‘kindness’ which tolerates anything except suffering in its object is, in that respect, at the opposite pole from Love.”[7] God wants us to experience the very best in life, which is him. But, in our natural state, we don’t seek him. That is particularly true when things are going well, when we seem to be in control of our lives. To know that God is God and we are not, we must come to the end of our illusion that we are at the center of the universe. We must come to the end of thinking that we’re God, that we’re in control. God uses pain and suffering to bring us into that position. As Lewis famously writes, “God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pains: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”[8]

So, after these words of warning in Amos, God says to Israel: “Seek me and live” (Amos 5:4). “Seek the Lord and live” (Amos 5:6). And,

14 Seek good, and not evil,

that you may live;

and so the Lord, the God of hosts, will be with you,

as you have said.

15 Hate evil, and love good,

and establish justice in the gate;

it may be that the Lord, the God of hosts,

will be gracious to the remnant of Joseph (Amos 5:14–15).

God tells the people to seek him, to seek good and forsake evil, so that they may live. Now, this doesn’t mean that we can return to God by doing good things. We cannot get to God through our own efforts. We know this from the rest of the Bible. Our sin, our rebellion against God, runs deep and it taints every part of us and everything we do. We can’t drive out the evil from within us. But if we seek God, we will want to do what is good.

But when we return to God, it’s more than just paying lip service. God wants more than just for us to do a few religious things. He wants our hearts. He wants changed lives. Look at Amos 5:21–24:

21 “I hate, I despise your feasts,

and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies.

22 Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and grain offerings,

I will not accept them;

and the peace offerings of your fattened animals,

I will not look upon them.

23 Take away from me the noise of your songs;

to the melody of your harps I will not listen.

24 But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

One of the sins of Israel was religious hypocrisy. They thought they could worship God and also worship other gods. They thought they could go through the motions by praying and singing and offering sacrifices to God, and then go and live like all the pagan nations around them. But that isn’t pleasing to God. In fact, God says he hates that. He hates religious festivals when they aren’t done from the heart. He hates singing, even songs that are about him, if it comes from unclean lips. He doesn’t want sacrifices made by people who aren’t sacrificing their whole lives. Instead, God wants people to love him and to live according to his word. That’s what justice is.

You may notice that Amos quotes Martin Luther King, Jr. here. That’s a joke, of course. Martin Luther King quoted Amos as a call to justice. But this justice isn’t just “social” justice. There’s only one form of justice in the Bible, and that is loving God and loving people the way that God wants us to. If we do justice in the public square but do immoral things in our private lives, that isn’t justice. It won’t do to provide for the poor and then engage in sexual immorality, for example. God isn’t impressed by that. He sees our condition. He demands righteousness.

And that leaves us in a bind. We aren’t perfectly righteous. We are not just. Even when we try to praise God, there’s still some taint of sin. Amos knew this. When he was shown visions of judgment in chapter 7, he says, “O Lord God, please forgive!”

How can we be forgiven by God? Perhaps the clue comes in Amos. In chapter 5, God says there will be a “day of the Lord,” a day of “darkness, and not light” (Amos 5:18). This will be a day of punishment, but it’s also a day of salvation. In chapter 8, we read these words:

“And on that day,” declares the Lord God,

“I will make the sun go down at noon

and darken the earth in broad daylight.” (Amos 8:9)

On the day of the Lord, a day of punishment and a day of salvation, the sun will go down at noon. Darkness will cover the earth at a time when there should be broad daylight.

This day of the Lord came almost three thousand years ago, when the only righteous man who ever lived, Jesus of Nazareth, was put to death. Jesus, the Son of God, was sent “to seek and to save the lost” (Luke 19:10). He came from a far-off country, from heaven, to bring people back to their God. He did this by living the perfect life that we should live but don’t, and then by dying in our place, taking the punishment for our sin that we deserve. When Jesus was crucified, darkness came upon the land at noon, a sign that he was enduring the wrath of God that we have earned. He didn’t do this for everyone. Only those who turn to Jesus in faith, who seek the Lord, are forgiven of their sins and will live with God forever.

We know Jesus is the one who brings us back home to God because in chapter 9 of Amos, God promises that after punishment, there will be a day of rebuilding. Look at Amos 9:11–12:

11 “In that day I will raise up

the booth of David that is fallen

and repair its breaches,

and raise up its ruins

and rebuild it as in the days of old,

12 that they may possess the remnant of Edom

and all the nations who are called by my name,”

declares the Lord who does this.

God promises to rebuild “the booth of David.” That’s a reference to David’s kingdom. David, the second king of Israel, was a great king. But David had already died, and his kingdom was divided. Yet God promised that a descendant of David would come and build a kingdom that will never end. This perfect king would defeat Israel’s enemies and bring about peace and justice that would last forever. We know from the New Testament that Jesus is that King. And he is calling a remnant of people “from all nations” into his kingdom. This passage is quoted in the Acts 15 when Jewish Christians are trying to figure out how Gentile Christians should live. The point is that the true Israel is everyone—Jew, Gentile, American, Chinese, black, white, male, female, rich, poor—who is united to Jesus by faith.

And those people will go home. They will live with God forever in a perfect world. Look at the end of the book, Amos 9:13–15:

13 “Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord,

“when the plowman shall overtake the reaper

and the treader of grapes him who sows the seed;

the mountains shall drip sweet wine,

and all the hills shall flow with it.

14 I will restore the fortunes of my people Israel,

and they shall rebuild the ruined cities and inhabit them;

they shall plant vineyards and drink their wine,|

and they shall make gardens and eat their fruit.

15 I will plant them on their land,

and they shall never again be uprooted

out of the land that I have given them,”

says the Lord your God.

This garden imagery reminds us of the garden of Eden, where humanity was first “planted.” We were kicked out of the garden because we didn’t love, trust, and obey God. How do we get back to the garden? Jesus. We’re told that he will come back to earth one day to make everything right. Those who trust in him will live in this perfect world. The images here are just a taste of what this perfect world will be like, a world of prosperity and pleasure. But most importantly, it will be home because our God dwells there.

Why do things like viruses occur? Why is the world disrupted economically? We could provide naturalistic answers, answers that only appeal to what we can see with our own eyes. Or, we could say, “Well, there’s no good reason.” Or, we could spend our time blaming politicians. But ultimately, God sends these things to get our attention. They are the megaphone he uses to rouse a deaf world. Are we listening? Are we turning back to God?

God lets us go our own way, running away from him to pursue our false gods. But God uses difficult events to bring us back to him. Will we answer his call? If you’re not a Christian, I urge you to turn to God while there is time. Learn about Jesus and follow him. If you want to know what that would look like in your life, send me a message and I’ll help you any way that I can. Christians, take God seriously. Don’t just pay him lip service. He deserves more than that.

Turn to God while there is time. If we continue to run away from God, he may very well let us go our own way—forever. And that will be a dreadful thing. Even in the book of Amos, there is a famine that is worse than lack of food, and there is a drought that is worse than lack of water. Amos 8:11 says,

“Behold, the days are coming,” declares the Lord God,

“when I will send a famine on the land—

not a famine of bread, nor a thirst for water,

but of hearing the words of the Lord.

The most horrifying thing is not to have God in your life, not to hear from him. Now, if you’re not a Christian, you may think that you don’t have God in your life and that you don’t hear from him now. But that’s not true. God is everywhere and all of creation speaks of God (Ps. 19:1–6). But there will be a day when all who have rejected God will be removed from him entirely. To be cut off from God means to be cut off from love, beauty, truth, light, and life. It’s worse than we can ever imagine.

But God has come to do everything you need to be put back into a right relationship with him. And right now, he is calling you back home. Come to Jesus, the truth, the life, and the way back to your God.

Notes

- C. S. Lewis, “The Weight of Glory,” in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses (New York: Harper One, 2001), 29. ↑

- Ibid., 30–31. ↑

- Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 3. ↑

- All Scripture quotations are taken from the English Standard Version (ESV). ↑

- Tremper Longman III and Raymond B. Dillard, An Introduction to the Old Testament, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 423. ↑

- C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (New York: Touchstone, 1996), 35–36. ↑

- Ibid., 36. ↑

- Ibid., 83. ↑

He Was Lost, and Is Found

This sermon was preached on July 7, 2019 by Brian Watson.

MP3 recording of the sermon.

PDF of the written sermon (or see below).

Throughout the history of religion, there have been two topics that have been disputed: who God is and how we should respond to him. In fact, if you study different religions, you will see that while religions teach similar things about ethics, they say very different things about what God is like and how we can have a right relationship with him. And throughout the history of Christianity, most heresies, or wrong teachings, have involved who God is and how we can be reconciled to him.

Today, we’re going to look at a story that gives us a glimpse of God’s character and how we should respond to him rightly. This story will also give us a picture of two wrong and very common ways to respond to God.

One of the things I do here is talk a lot about the gospel of Jesus Christ. I teach the message of Christianity so that we understand it and can tell it to others. I encourage us all to share this news with others. And I encourage us all to live in light of the gospel. So, what I’m preaching here today isn’t going to be very new to you, unless you’re very new to church and to the Bible. But what matters most is not whether I teach something new, but whether I teach something that is true. And the fact is that whether you’re someone who is not yet a Christian, or you’re the most seasoned saint, we all need to hear the gospel, time and again, to learn it, remember it, and press it deeply into our minds and down into our hearts so that it affects the way we live. As Tim Keller has written, “The gospel is . . . not just the ABCs of the Christian life, but the A to Z of the Christian life.”[1] The gospel isn’t something we learn once and then leave behind for more important things. The gospel is the main event, not the undercard. It’s the headliner, not the opening act.

To experience the gospel once again, today we’re going to look at Luke 15. As we do that, we’re going to see a few important things. We’re going to see that there are two wrong ways to respond to God. We’re going to see that there is a right way to respond to God. We’ll see the heart of God. And we’ll see Jesus, his mission, and our mission.

Let’s begin by reading the first two verses of Luke 15:

1 Now the tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear him. 2 And the Pharisees and the scribes grumbled, saying, “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”[2]

It’s important to see that Jesus is speaking to two groups of people here. The first group are the tax collectors and “sinners.” Tax collectors had a bad reputation. They were Jews who collected taxes for the Roman Empire. As you may know, during the time of Jesus, Palestine was under Roman rule. This meant that Jewish tax collectors were viewed as something like traitors. Tax collectors also had a reputation for being dishonest, collecting more money than they should (Luke 3:13). So, tax collectors are often lumped together with “sinners.” In the Pharisees’ view, “sinners” were people who didn’t keep their standards of purity—standards added to God’s commandments. “Sinners” could also refer to people who rather obviously broke God’s commandments.

But these people came to hear Jesus. Jesus had a message that attracted people who had made a shipwreck of their lives. He gave them hope, and they wanted to hear more.

The other group of people Jesus is talking to are the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, or the scribes. They represent the religious leaders of Judaism. Up to this point in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus has had a lot of conflict with these religious leaders. Jesus says they’re greedy hypocrites who care only about appearing religious while in reality their hearts are corrupt (Luke 11:37–52). They try to justify themselves before God by appealing to all their religious works (Luke 18:9–14). They adhere to the letter of the law while missing the heart of God’s commandments, which is simply to love God and to love other people.

We’re told that the Pharisees and the scribes are grumbling. That’s a loaded word in the Bible. It’s used of the Israelites when they complained about Moses after they were delivered out of slavery in Egypt.[3] So, Luke is showing that these people are aligned with those faithless, disobedient Israelites. They complained that Jesus hung out with “sinners” (Luke 5:30–32), and they were out to get him (Luke 11:53–54).

All of this is very important to understanding what Jesus teaches in this chapter. Jesus then tells this audience a parable. Notice that chapter 15 is one parable in three parts. I’m going to spend most of my time on the third part, but let’s first read verses 3–10:

3 So he told them this parable: 4 “What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the open country, and go after the one that is lost, until he finds it? 5 And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing. 6 And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.’ 7 Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.

8 “Or what woman, having ten silver coins, if she loses one coin, does not light a lamp and sweep the house and seek diligently until she finds it? 9 And when she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbors, saying, ‘Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin that I had lost.’ 10 Just so, I tell you, there is joy before the angels of God over one sinner who repents.”

I think the point of these stories is clear: “sinners” are worth seeking. In both stories, something precious is lost, someone goes searching for what was lost, and when the lost is found, there is great rejoicing. Jesus says that’s the way it is when sinners, people who were separated from God, are found by God, when they turn away from their sin and turn back to God.

It seems like Jesus is telling the religious leaders that they should be searching for the lost, not grumbling when they come to God.

Then Jesus tells what is often called “The Parable of the Prodigal Son.” The parable might better be called, “The Parable of a Father and His Two Sons,” though that isn’t as catchy. But this parable is as much about the older son as it is the younger son. First, we’ll see what happens with the younger son. Let’s look at verses 11–16:

11 And he said, “There was a man who had two sons. 12 And the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of property that is coming to me.’ And he divided his property between them. 13 Not many days later, the younger son gathered all he had and took a journey into a far country, and there he squandered his property in reckless living. 14 And when he had spent everything, a severe famine arose in that country, and he began to be in need. 15 So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his fields to feed pigs. 16 And he was longing to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate, and no one gave him anything.

The younger son approaches his father and asks for his inheritance now. That’s shocking. What would you be doing if you asked your parents for your inheritance now? You’d be saying that you wished they were dead so you could take their money. He doesn’t want his father; he wants his father’s stuff. Amazingly, the father obliges. In Jewish law, the eldest son inherited a “double portion,” twice as much as the other sons. In this case, the younger son would have inherited one-third of all the father’s possessions.[4] The father gives this to the son, who then leaves for “a far country.” There, the son engages in “reckless living.” He lives it up and he squanders everything that his father has given him.

In this parable, the father obviously represents the Father, God. And the attitude this younger son has is one wrong response to God. We might call this licentiousness or law-breaking. If you want to know the story of the Bible and the story of humanity in a nutshell, you can find it in this story. God is a perfect Father who created the world and all that is in it. He made us in his image, to reflect his glory and to serve him, and he made us after his likeness, which he means he made us to be his children, to love him and obey him the way children should love and obey a perfect father. But from the beginning, people have said to God, “We don’t want a relationship with you. We want your stuff. Go away. We’ll call you if we need anything else.” The first humans didn’t trust that God was good, they wanted something other than what God had given them, and they were banished to a far country where they found famine and death. And that’s our story, too. We live in his world, we enjoy his blessings, but we don’t really want him. The heart of sin isn’t just breaking God’s commandments. The heart of sin is a rupture in our relationship with God. So, we, too, find ourselves in a distant country. We’re exiles. That’s why we often don’t feel at home in this world.

Now, back to the parable: When the son has spent everything, a famine occurs. He has no one to turn to. There’s no family around. So, he becomes a hired hand, working for a Gentile, feeding pigs. Things were so bad for him, he wished he could eat the pigs’ food. Pigs were unclean animals (Lev. 11:7; Deut. 14:8). He was unclean, lower than the pigs. This would indicate to a Jewish audience that this son could go no lower. He had reached bottom.

But then comes a change. We see this beginning in verse 17:

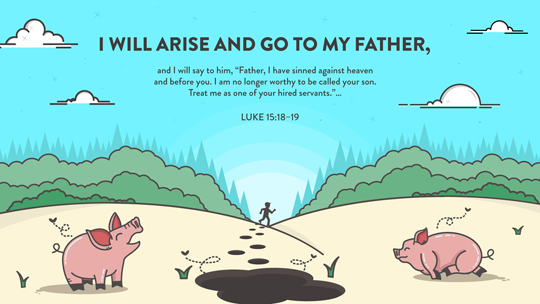

17 “But when he came to himself, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have more than enough bread, but I perish here with hunger! 18 I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. 19 I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired servants.”’

The son comes to his senses! Before, he wasn’t thinking rightly. He decided he could have a better life apart from his family. But once he hit bottom, he woke up to the truth. So, he prepares a little speech. He will tell his father that he sinned “against heaven”—this is another way of saying he sinned against God. And he sinned against his father. He realizes that because of this, he is not worthy to be called a son. He asks merely to be a hired hand.

This is the right response to God. We must realize that because of our sin, we are not worthy to be called God’s children. We must confess our sin and turn back to God, appealing only to his grace. This is what repentance looks like: coming to our senses. We had once exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and our thinking was futile (Rom. 1:18–25). But when we come to see who God is and who we are, we come to our senses and turn back to God.

When we turn to God, he welcomes us back home. In this story, we already saw that the father let the son go his way. Now we see him welcome his son back home. This represents the loving character of God. I’ll read verses 20–24:

20 And he arose and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. 21 And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ 22 But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet. 23 And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate. 24 For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to celebrate.

The prodigal son returns home, and as he approaches, his father sees him. The father is filled with compassion and he can’t wait to be with his son, so he runs. He doesn’t care about how he looks or what anyone might think about him. The father embraces the son; he doesn’t wait for an apology or a confession. But the son does confess, repeating much of the speech he recited earlier.

Yet the father doesn’t say, “You’re right: you’ve sinned!” There is no penalty. There is only acceptance. The father asks his servants to put his best robe, a ring, and sandals on the son. These things illustrate that the son is received back into the family. His relationship with his father is restored. And this is celebrated. The father calls for a feast to be prepared. This would have been a very rare occasion, because a fattened calf was expensive. The whole village was probably invited to this feast. Why does the father celebrate? “For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.”

When sinners turn from their sin and put their faith in Jesus, they become spiritually alive. We once were dead in our transgressions and sins (Eph. 2:1), but now have been made alive with Christ (Eph. 2:5). We once were lost, but now we’re found. This is a great reason to celebrate.

The idea of a feast is fitting, because eternity with God is sometimes described as a feast. One day, Jesus will come again to judge the living and the dead, and all who have put their trust in Jesus will live with God forever in a new world, a world in which all evil is removed. The idea of a feast is far more than just eating a lot of good food. It’s being welcomed into God’s home, joining him at his table. It’s communing with God, sharing in his abundance. In fact, the Bible even says that when this great feast is served, it will never end. It won’t end because when the feast is served, death itself will be removed (Isa. 25:6–9).

Now, if we stopped here, it would be a nice story, but we would miss one of the major points of this parable. So, we must see how the elder son reacts. The elder brother shows us another false response to God. One way to reject God is to be like the younger brother, to break all the rules, to seek meaning in life through entertainment and pleasure, to squander everything in “reckless living.” But there’s another way to reject God, and this may come a little closer to home. Let’s look at verses 25–32:

25 “Now his older son was in the field, and as he came and drew near to the house, he heard music and dancing. 26 And he called one of the servants and asked what these things meant. 27 And he said to him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fattened calf, because he has received him back safe and sound.’ 28 But he was angry and refused to go in. His father came out and entreated him, 29 but he answered his father, ‘Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command, yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends. 30 But when this son of yours came, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fattened calf for him!’ 31 And he said to him, ‘Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32 It was fitting to celebrate and be glad, for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found.’”

When the older son hears that his brother his home, he doesn’t come running. Instead, he gets angry and he refuses to join the feast. Why is the brother angry? It’s possible that he thought he might lose part of his inheritance. Before, he was to receive two-thirds of his father’s estate. But his younger brother is now restored. That suggests that the younger son might get a third of the current estate. If that’s true, then the older brother just lost a third of his inheritance.

But perhaps the brother is simply jealous of his brother. Look at how he talks to his father. He says, “I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders. But you’ve never celebrated that. You’ve never even given me a little goat.” It looks like he resents the attention his brother is getting. He calls his brother “this son of your yours,” and he says his brother wasted money on prostitutes. How did he know that? Was he speculating, or did he hear it through the grapevine? At any rate, he’s angry and resentful.

Perhaps the older brother thinks his father is playing favorites. At any rate, this doesn’t appear fair to him. Sometimes, people don’t think the gospel is fair, but they don’t understand that it would be fair for God to condemn all of us for our sin. But he doesn’t. That’s mercy. Sometimes, people don’t understand the point of grace: no one deserves salvation. That’s why it’s grace—it’s a gift.

Now, if you haven’t figured it out yet, the younger brother represents the tax collectors and the sinners, and the older brother represents the Pharisees and the scribes. The first group of people had sinned, but they were coming to Jesus. They were coming home. The second group was grumbling, like the older brother. You see, there is a very religious way to reject God. We might call this legalism. You can try to earn God’s favor. You can try to obey all the rules. You may even think God owes you something for all your work. But if you are merely trying to earn something from God, you don’t really want God. You don’t really love him. But God doesn’t just want our obedience. He wants our hearts. He wants a relationship with us. This older brother looks like he didn’t care about his relationship with his father. By not coming to the feast, he was dishonoring his father. He was so consumed with working to earn his inheritance that he rejects his father and his brother.

If we fail to see that salvation is by God’s grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone, we will become like the older brother. If we believe we are Christians because we’re good people, because we’re moral, we may be in greater danger than the “sinners” around us. Christianity is not moralism. Christianity doesn’t say, “If you’re good enough, you can get to God.” That’s what a lot of other religions say. Christianity say something more shocking. It says “You’ll never be good enough to earn God’s favor. Your best deeds are polluted by selfish motives and your sin (Isa. 64:6). In fact, you’re so bad that God had to become man and die in your place.” But that’s the great thing: Jesus did that for us. The Father loves us so much he would send his Son, and the Son loves us so much that he would leave his home and go to a distant country to seek and save the lost (Luke 19:10).

That’s brings me to Jesus. Of course, Jesus is telling this story. But the story hints at what Jesus himself does. You see, the first two parts of this story were about someone finding something precious. A shepherd goes to find a lost sheep. A woman searches for a lost coin. You would expect that in the third story, someone goes to find something. But that doesn’t happen.

If you think more about it, it seems that the older brother should have been the one to go find the younger brother. The father might have been too old, or too busy managing his property, to go and seek his youngest son. But the older brother knew that his brother was living a life of sin, and he didn’t seem concerned. Again, he was too busy trying to earn something from his father to leave and find his brother.

But perhaps the older brother of this story isn’t the true older brother. Perhaps Jesus doesn’t tell us about someone going to find the younger brother, because he wants us to see that he is the one who has come to find his younger brothers. Later in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus describes his own mission: “the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost” (Luke 19:10).

There’s another way to see that this story is about Jesus. The story doesn’t tell us the basis for salvation. But perhaps it hints at it. I said earlier that Jewish law states that the eldest brother gets a double share of the inheritance. That law is found in Deuteronomy 21:15–17. But I want us to look at what comes right after that passage. Deuteronomy 21:18–21 says a rebellious son deserves death:

18 “If a man has a stubborn and rebellious son who will not obey the voice of his father or the voice of his mother, and, though they discipline him, will not listen to them, 19 then his father and his mother shall take hold of him and bring him out to the elders of his city at the gate of the place where he lives, 20 and they shall say to the elders of his city, ‘This our son is stubborn and rebellious; he will not obey our voice; he is a glutton and a drunkard.’ 21 Then all the men of the city shall stone him to death with stones. So you shall purge the evil from your midst, and all Israel shall hear, and fear.

The younger son in Jesus’ story deserved to die, according to this law. And the older son, with his own rebellious heart and his refusal to come to the feast, deserved death, too. We’re all like those sons, stubborn and rebellious children who deserve the death penalty for our sin. But if you are a Christian, you have received eternal life. How is that possible? Look at the next two verses (Deut. 21:22–23):

22 “And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, 23 his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is cursed by God. You shall not defile your land that the Lord your God is giving you for an inheritance.

Now, if you don’t see Jesus there, don’t worry. It’s not immediately obvious, by any means. But the apostle Paul, in Galatians 3:13, quotes part of that passage to show how we are reconciled to God. He writes, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree.’” When Jesus died on the “tree”—the cross—he died so we don’t have to receive God’s wrath. He paid for all our sins on the cross. He sought us and bought us with his precious blood. If we have faith in Jesus, he is our true elder brother.

You’ll notice that the parable ends without a response from the older brother. Jesus is pleading with the Pharisees and scribes to come to the feast, to surrender their pride and rely only on God’s grace.

And I’ll end by pleading with you. I don’t know if we have any younger brothers here today, because I don’t know you all personally, and I can’t see your hearts. If you’re seeking meaning in life by breaking all the rules, if you’re trying to be your own god, if you think you’re the ultimate authority in your life, I promise you that path will only lead to destruction. Running away from God may feel fun for a while, but this reckless living will leave you empty, and you’ll find yourself in the muck and mire, far from home, without comfort and hope. I urge you to come to your sense, to come home to God, to turn to Jesus.

I think it’s far more likely that there are older brothers here. If you’re an older brother, you may look down at other people. You may be bothered if a messy “sinner” comes to church on Sunday. You might think God owes you something for all your years of service. You may resent it when things don’t go your way. We should rejoice when sinful people show up at the church. My hope is that you’ll see more of those people here in the future.

If you’re neither a younger brother nor an older brother, but if you’re a true child of God, then consider how you can be like Jesus. He came to seek and save the lost. What are you doing—what are we doing—to seek and save the lost around us? Jesus’ brother, James, writes this at the end of his letter: “My brothers, if anyone among you wanders from the truth and someone brings him back, let him know that whoever brings back a sinner from his wandering will save his soul from death and will cover a multitude of sins” (James 5:19–20; see also Gal. 6:1). We should go after people who have wandered from the truth. We should go after people who have never known the truth. Start with prayer. Ask God to bring people who need Jesus into your life. Think about the people around you who aren’t yet Christians and pray for their souls. Pray for opportunities to talk to them about Jesus. And, when the opportunity is right, plead lovingly with those around you to consider Jesus.

My hope is that this church would be one that sees younger brothers coming to their senses, but this can only happen if we aren’t older brothers. Start praying that people around you would come to your senses. Seek them out, love them, tell them the good news about Jesus, and invite them to the feast.

Notes

- Timothy Keller, The Prodigal God: Recovering the Heart of the Christian Faith (New York: Dutton, 2008), 119. ↑

- All Scripture quotations are taken from the English Standard Version (ESV). ↑

- Exod. 15:24; 16:2; 17:3; Num. 14:2; 16:41. ↑

- Deut. 21:15–17. ↑

He Was Lost, and Is Found (Luke 15)

There are two wrong ways to respond to God: to run away from him and break all the rules, or to try to earn favor from him by obeying all the rules (and for selfish reasons). But there is a right way to respond to God, and when we turn to him, he is like a loving father who welcomes us back home. Brian Watson preached this message on Luke 15 on July 7, 2019.