This sermon was preached on September 8, 2019 by Brian Watson.

MP3 recording of the sermon.

PDF of the written sermon (or see below).

Let’s imagine something for a moment. Imagine you have a job. For some of you, this isn’t all that hard to do. Imagine that your company was recently purchased by a new owner, who has brought in new management. The new management announces that they are going to interview everyone who works for the company. They present this as a “getting-to-know-you” exercise. They schedule interviews with every single employee, including you. At beginning of your interview, they ask you simple questions about you, such as what your role in the company is, how long you’ve worked there, where you went to school, what other kinds of experience you have—that sort of thing. Then they ask you what you do at the company. As they start to ask more specific questions, it dawns on you that they’re not just trying to get to know you. They’re trying to see if they want to continue to employ you. In short, they’re asking you to justify your position with the company. So, you start to give answers that you would give when you interview for a job. You tell them how you work hard, how much experience you have doing your job, how productive you are, how well you get along with your coworkers, and anything else you can think of to convince them that they should keep you on the payroll.

That’s a bit of what “justification” looks like. It means something like an acquittal. Being justified means being viewed as not guilty, as innocent, as in the right, as acceptable. Justification is a big word in Christianity, and we don’t always hear about it in other contexts. But the fact is that we all try to justify ourselves in some way or another. We try to demonstrate that we’re in the right, that we’re good people, that we have the right beliefs and the right behaviors, that we’re people who should be accepted and embraced.

The key question that we all should ask is, How can I be acceptable to God? What sort of justification can I offer to him? We should think along those lines, but there are many people who don’t even realize that we need to be justified in the presence of God. But we do need justification. We need something that makes up for our sin, that reconciles us to God, that shows that we’re acceptable to him, that we’re worthy. What are you relying upon for justification?

Today, as we continue our study of the Gospel of Luke, we’re going to see a famous parable that Jesus tells, a story about two people who come to the temple to pray to God. These two people have very different attitudes, and they make two very different speeches. Jesus tells us that only one of them is justified.

Let’s now read today’s passage, Luke 18:9–14:

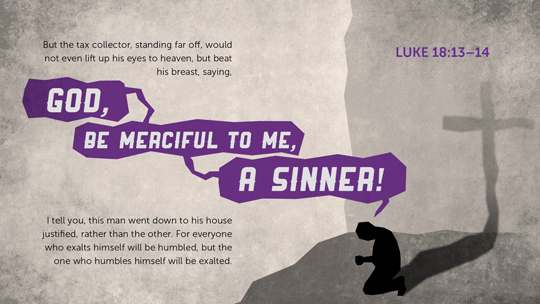

9 He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt: 10 “Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. 11 The Pharisee, standing by himself, prayed thus: ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. 12 I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I get.’ 13 But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ 14 I tell you, this man went down to his house justified, rather than the other. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted.”[1]

Luke tells us up front why Jesus tells this story: Jesus has in mind people “who trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and treated others with contempt.” That kind of mindset is opposed to the way of Jesus for two reasons. One, Jesus repeatedly says in different ways that no one is righteous. So, to believe that one is righteous, without sin, not in need of mercy, is to be deceived. Two, those who treat others with contempt fail to see that other people are made in God’s image and likeness. We have no right to act as if we are superior to others, particularly if we realize our own unrighteousness. Jesus probably is addressing this story to the Pharisees, a group of religious leaders who were known for their strict adherence to the Hebrew Bible.

The story itself has a setting and two characters. The setting is the temple in Jerusalem. This is where God was worshiped, where sacrifices for sin were offered, and where people prayed. We don’t know if this was one of the twice-daily times of prayer at the temple (at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m.) or if the men just happened to go to the temple at the same time to pray individually. The point is that both were going to meet with God.

Then, we are told about the two characters of the story. The first is a Pharisee. There were a few groups of Jewish religious leaders at this time. There was the high priest, as well as the many priests who served at the temple. Then there were two groups of influential Jews. One was the Sadducees, who had more political power but who had unorthodox beliefs. Famously, they didn’t believe in the resurrection of the dead. The other group was the Pharisees, who were lay leaders known for taking the Hebrew Bible, what we call the Old Testament, very seriously. They were very disciplined in their approach. They tried to apply the whole Bible to all of life in very specific, rigorous ways. The apostle Paul, before becoming a Christian, was a Pharisee, and he had previously boasted of his adherence to the law (Phil. 3:4–6).

But Jesus has criticized the Pharisees repeatedly for being hypocrites, for not seeing their own lack of righteousness, and for using their positions of privilege to earn money. In short, the Pharisees don’t come out looking good in this Gospel.

The Pharisees have grumbled that Jesus would spend time eating and drinking with obviously sinful people. In Luke 5:30–32, we read this:

30 And the Pharisees and their scribes grumbled at his disciples, saying, “Why do you eat and drink with tax collectors and sinners?” 31 And Jesus answered them, “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. 32 I have not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance.”

Jesus came to save people from their sin. Sin is a sickness, a rebellion against God but also a powerful, evil force that finds its way into everything we do. The only people who go to a doctor for healing are those who are willing to admit they are sick and need help. The Pharisees still wrestled with sin, but they had lost sight of that fact. They acted as if they were truly righteous and everyone else was not.

We’re told that this Pharisee stood by himself when he prayed. We don’t want to read much into that. There are times when people stand while praying in the Bible (1 Sam. 1:26; 1 Kgs. 8:22). But perhaps he was by himself because he thought he was above everyone else.

At any rate, we are given his prayer. It consists of twenty-eight words in the original Greek. He begins well: “God, I thank you.” It’s good to begin prayers by thanking God. But look what he thanks God for: “God, I thank you that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I get.” He’s basically praying, “God, I thank you that you made me so great. When you made me, you did an excellent job. I’m not like those other sinners. I’m nailing it when it comes to all the religious things.”

The Pharisee thanks God for not making him like sinners. He even is so bold as to point out the tax collector, the other character in this story. “I thank you that I’m not like that poor slob over there.” Tax collectors had a bad reputation for two reasons: one, they often took more than they needed to take. In an era before computers or advanced paperwork, it was easy to tell people they owed more than they actually did. But, perhaps more importantly, tax collectors worked for the Roman Empire. They were Jewish people working for the enemy, the superpower of the day, the occupying force that oppressed Jews. Tax collectors were not only dishonest, but they were traitors. That’s what this Pharisee surely thought.

What the Pharisee is doing is comparing himself to other people. As he thinks about other people, he is evaluating his own moral performance against theirs. By that standard, the Pharisee comes out well. He’s thinking, “I’m not as sinful as them.” He also boasts about his good deeds. He fasted twice a week. Fasting might mean consuming only water and bread (Shepherd of Hermas 5.3.7). The Jews were only commanded to fast on the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur (Lev. 16:29; Num. 29:7). They might also fast when mourning or repenting. Pharisees were known to fast on Mondays and Thursdays. They went above and beyond what the law required.

The Pharisee also claims to tithe everything he gets. Israel was supposed to over various tithes of their produce (Num. 18:21–24; Deut. 14:22–27). A tithe literally means a tenth, though if you added Israel’s tithes, they were supposed to give something like 23.3 percent of their crops. Perhaps the Pharisee is saying that he tithes all his income, or perhaps he means that for everything he spends—for all the stuff that he “gets”—he gives ten percent away. At any rate, he’s bragging about how much he gives to the temple.

Though the Pharisee begins by praying to God, the “prayer” is really all about him. He’s the subject: I thank you, I’m not like other men, I fast twice a week, I tithe everything. I, me, mine.

The other character in this story is the tax collector. I’ve already explained their reputation. It was not good. The Pharisees complained that Jesus ate with such sinners (Luke 5:30) and would spend time with them (Luke 15:1–2). Yet this tax collector humbly makes his way to the temple. Given their reputation, it’s not unreasonable to think that tax collectors didn’t go to the temple often, perhaps because they wouldn’t want to go, perhaps because they knew how they would be viewed by others.

Like the Pharisee, the tax collector stands. But he stands at a distance. The Pharisee might have gone right into the courtyard of the temple. This tax collector was standing “far off,” perhaps on just the edge of the temple complex. Though some people prayed while looking up to God (Ps. 123:1; Mark 6:41; 7:34; John 11:41; 17:1), this tax collector can’t do that. He feels unworthy to look directly toward God. He beats his breast, a sign of mourning. And he simply says, “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” In the original Greek, his prayer is only six words (compared with the twenty-eight words of the Pharisee).

Now, I don’t often play the “in the Greek . . .” card, but I will here, because it’s important. The way that the tax collector’s prayer is translated hides a couple of important details. First, he literally says, “God, make atonement for me.” He knows he needs God’s mercy. But the way to get mercy from God is if atonement is made. The Greek word used here is also used in Hebrews 2:17, where we’re told that Jesus made “propitiation for the sins of the people.” To be right in God’s eyes, to be acceptable to God, to be forgiven by him, he needs someone who can make God propitious towards him. In other words, he needs someone who can make God look favorably upon him. This man knows that he has nothing to bring to God that can turn away God’s judgment against his sin. He confesses that he’s a sinner. He doesn’t brag about who he is or what he’s done. He simply knows that he needs atonement for his sin, and he knows that God must be the one to atone for his sin. No amount of good works can make up for the sin that he’s committed.

The other interesting detail that is found in the original Greek text is that this man says, “God, make atonement for me, the sinner.” He doesn’t say “a sinner.” Instead, he says, “the sinner,” using the definite article. Why does that matter? It’s like he’s saying, “I’m not comparing myself to other people. I’m not saying that I’m just another sinner, like everyone else around me. I am the sinner who needs atonement for his sins.” The Pharisee compared himself to others and did so favorably: “I’m better than everyone else.” But this tax collector isn’t comparing. He’s not judging himself by that standard. Instead, he’s judging himself against God’s standard. It’s like when the apostle Paul called himself “the foremost” sinner (1 Tim. 1:15).

These two men couldn’t be any more different in their stature in society and in their attitudes. Yet in verse 14, Jesus provides the twist: the tax collector and not the Pharisee went back home justified. The tax collector found favor in God’s eyes. The Pharisee did not. Jesus gives the reason why: For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” This is like so many of the twists that we see in Jesus’ parables: the Samaritan, not the priest or the Levite, was the one who loved his neighbor (Luke 10:25–37); the younger sinful brother came back home and was embraced by his father while the older righteous brother stayed outside (Luke 15:11–32); the rich men went to hades while the poor men went to paradise (Luke 16:19–31).

There are three truths that I want us to see from this parable. The first truth concerns the attitude we should take in approaching God. The tax collector had it right. He humbly approaches God and seeks forgiveness that only God can give. He seeks a solution to his sin that he cannot possibly provide, but that God can. He acknowledges he’s a sinner. He doesn’t compare himself to anyone else. He knows that he stands in need of God’s mercy.

The Pharisee isn’t really praying to God at all. His prayer is really a boast. He compares himself with others and, since he’s relatively obedient to the law, he thinks he’s superior to others. He looks down at “this one,” this tax collector. He brags about all the good things he has done. There’s no awareness that he, too, is a sinner standing in need of atonement. He is justifying himself, assuming that all his good works have put him in the right before God.

The right attitude before God is captured in King David’s famous confession of sin, which we find in Psalm 51. King David had committed adultery, then when he found out the woman was pregnant, he tried to cover up his sin by arranging for her husband to sleep with her. When that didn’t work out, he had the husband killed. (See 2 Samuel 11 for the story). When the prophet Nathan called him out for his sin, David confessed that he had done what was wrong, and he asked God for forgiveness (2 Sam. 12:1–13). Look at Psalm 51:1–4:

1 Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

2 Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin!

3 For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me.

4 Against you, you only, have I sinned

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you may be justified in your words

and blameless in your judgment.

David knew that he had ultimately sinned against God, and that he needed God’s mercy. God would be justified in condemning David, but David appealed to God for mercy. He confessed his sin and he found healing and forgiveness.

Later in the same Psalm, David says (in verse 17):

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

He knew that what God wanted was a sign of repentance, a broken spirit and a contrite heart, a godly remorse over sin. God doesn’t want pride and boasting. He wants people to realize what they have done, and to come to him humbly and in faith.

That is the attitude a sinful person should have before God. And the fact is that all of us have sinned. We have all failed to love God as we should. We have failed to obey his commandments. We have failed to love other people as we should. We have even failed our own moral standards and moral codes. We have done wrong, and God knows it. He would be justified to condemn us. We must seek the atonement that only he gives.

Of course, not everyone realizes this. Just this past week, I happened to catch a bit of a video clip from an interview between Ben Shapiro and Bishop Robert Barron. If you don’t know who Ben Shapiro is, he’s a relatively young man who is a significant conservative figure. He’s a lawyer, an author, a writer, and a host of a very popular podcast. He’s made appearances on CNN and other television channels. He’s also an Orthodox Jew. So, he had this interview with a Catholic bishop, and at one point, Shapiro asks this question: “What’s the Catholic view on who gets into heaven and who doesn’t?” Then, he immediately adds, “I feel like I lead a pretty good life, a very religiously based life in which I try to keep not just the Ten Commandments, but a solid 603 other commandments as well. And I spend an awful lot of my time promulgating what I would consider to be Judeo-Christian virtues, particularly in Western societies. So, what’s the Catholic view of me? Am I basically screwed here?”[2]

I like Ben Shapiro. I agree with many things that he says. But what he’s doing there is very similar to what the Pharisee does in the parable. He’s claiming that he lives a good life. Actually, Shapiro hedges that a bit to say he lives “a pretty good life.” He claims that he tries to keep the 613 commandments of the Old Testament. (I’m not sure how he keeps all the commandments related to worshiping at the temple in Jerusalem and offering animal sacrifices.) But I doubt that he does well even with the Ten Commandments. Who has not coveted (Exod. 20:17)? Who hasn’t put something before God in their lives (Exod. 20:3)? Who has always loved God with all one’s heart, soul, and might (Deut. 6:5)? Who has always loved one’s neighbor as one’s self (Lev. 19:18)? Shapiro doesn’t seem to think he has sins that he can’t make up for.

The Bishop says that Shapiro is not “screwed.” He says that the Catholic Church has taught since Vatican II that people other than Christians can be saved if they follow their conscience. Jesus is the privileged path to salvation, and he must be followed, but the Bishop waters down what that means. He says that the atheist who follows his conscience is actually following Christ, though he doesn’t know it.

Then, Shapiro asks the Bishop if Catholicism is faith-based or acts-based. Shapiro acknowledges that Judaism is an acts-based religious, “where it’s all about what you do in this life, and that earns you points in heaven.” The Bishop says that Catholicism is “loved-based,” which is a nice answer. He does say that Catholicism requires faith, but it is perfected by works. He rightly acknowledges that a relationship with God begins with grace, and that it requires a response that includes obedience, but he suggests that human effort contributes to salvation.

Those are two wrong ways of looking at salvation. This leads me to what Jesus didn’t teach clearly in this parable, and this is the second truth that we should know this morning. How is one saved? What is the basis of salvation? If it’s true what the Bible says, that all of us have sinned (Rom. 3:23) and that even our best acts of righteousness are tainted by sin (Isa. 64:6), how can we be saved? The parable makes it clear that we must go to God humbly and ask for mercy. But how does that work?

God is a righteous judge who must punish sin. He promised punishment and exile for sinners. How can God punish sin without destroying all sinners?

God also desires righteous members of his covenant. He demands a righteous people. How can we be declared in the right, innocent, as if we had never sinned but had only done what he wants us to do?

The answer is Jesus. He is the only truly righteous person who has ever walked the face of the earth. He is the God-man, forever the Son of God, yet who added a human nature over two thousand years ago. He alone loved God the Father (and God the Spirit) with his whole being. He alone has never failed to love his neighbor. He alone has obeyed all the commandments.

Yet Jesus died a sinner’s death, bearing the wrath of God when he died on the cross. He was treated like the worst of criminals though he never did anything wrong. He then rose from the grave on the third day, to show that he paid the penalty for sin in full and to demonstrate that all his people will rise from the grave on day when he comes again in glory. If we trust in him, our sins have already been punished. The apostle wrote to the Colossians that “you, who were dead in your trespasses . . . God has made alive together with him, having forgiven us all our trespasses, by canceling the record of debt that stood against us with its legal demands. This he set aside, nailing it to the cross” (Col. 2:13–15). If we have faith in Jesus, if we trust that he is who the Bible says he is and he has done what the Bible says he has done, our sin is paid for, and we are credited with his righteousness.

This can only be accessed by faith, not works. In his letter to the Galatians, Paul writes,

15 We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; 16 yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified (Gal. 2:15–16).

Paul makes this abundantly clear in Romans, as well as in Galatians and Philippians and his other letters. In Ephesians, he famously writes,

8 For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, 9 not a result of works, so that no one may boast (Eph. 2:8–9).

Paul also says that we should do the good works that God has prepared in advance for us (Eph. 2:10), but those good works are not the basis for our salvation. They are not the root of our salvation, but the fruit that naturally comes out of life changed by Jesus and the Holy Spirit.

If we have a right relationship with Jesus, one marked by trust, love, and obedience, we will know who he is. We might not know everything, but we do need to know some things. Importantly, we will know that he is God. In John 8:24, Jesus told the Jewish religious leaders of his day, “I told you that you would die in your sins, for unless you believe that I am he you will die in your sins” (John 8:24). “I am he” is a reference to the God of the Old Testament. It is how God referred to himself when he first spoke to Moses (Exod. 3:14). It is how God refers to himself in the book of Isaiah (Isa. 41:4; 43:10, 25; 45:18; 46:4).

The Bible pictures salvation as being united to Jesus. The Bible also says that Jesus is our bride. If you are married to someone you will know it, and you will know important things about your spouse. So, if you’re married to Jesus, you’ll know that he’s the Son of God, the world’s only Savior, and the King of kings and Lord of lords. You’ll know that he died on the cross for your sins and that he rose from the grave.

The third truth I want us to think about is that we will stand before God on judgment day. We will have to give an account for what we have done. I don’t know the mechanics of how this will work out. I don’t know that we’ll be given a chance to speak to God and present a case for our justification. But let’s say we will. What will you say to God? Will you say, “God, I deserve to be with you for eternity because I’ve done all these good things. I’ve prepared a PowerPoint presentation to show you all the good things that I’ve done.” Or will you humbly say something like this? “God, I know that you would be right to condemn me. I know that I have failed to love you and to obey you. Have mercy on me, the sinner. Please forgive me. My only hope is your Son, Jesus. I trust that his righteousness and his atonement are enough to save me from sin. My faith is set upon Christ. He is my only hope for salvation.” If that is the posture of your heart, you have faith in Jesus. The good news is that he can save us from any sin we’ve committed. We can be acceptable to God because of Jesus. But we must first acknowledge our sin and humbly seek forgiveness. We must repent, turning away from sin, and turn to our only hope, who is Christ.

Christians, we must not look down at other people as though we were better than them, or more deserving of God’s grace. We must not say, “God, I thank you that I’m not a Democrat,” or, “God, I thank you that I’m not a Republican.” We can’t even say, “God, I thank you that I’m not like that Pharisee.” We must not boast in ourselves, but we must boast in Christ. Paul wrote, “Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord” (1 Cor. 1:31; 2 Cor. 10:17; quoting Jer. 9:24). He then wrote, “For it is not the one who commends himself who is approved, but the one whom the Lord commends” (2 Cor. 10:18).

Notes

- All Scripture quotations are taken from the English Standard Version (ESV). ↑

- The interview can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0oDt8wWQsiA&feature=youtu.be. The relevant portion of the interview begins at about 16:20. ↑