This sermon was preached by Brian Watson on October 23, 2016.

MP3 recording of the sermon.

PDF of the written sermon (see also below).

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been looking at some important things that we do in the church. And today, I want to talk about something we do every single week. I want to talk about music.

I don’t think I need to tell you that music is an important part of life. We hear it everywhere: On the radio, on soundtracks to movies and television shows, on commercials, and, yes, in the church. Yet we don’t often spend time talking about music, what it means, and why it’s important.

So, today I want to do that. I want to help us think Christianly about music. More specifically, I want us to think about the role of singing in the life of the church. To do that, I’m going to ask and answer a series of questions.

Here’s the first question: Why do we sing? Maybe that sounds like a funny question to ask. Perhaps some of you are thinking, “Why shouldn’t we sing?” But it’s an important question to ask. I think that public singing is a lot less common than it used to be. There’s only one place outside the church and outside choirs where people tend to sing in public, and that’s at rock concerts. We don’t sing in the mall, at the movie theater, or at sporting events. (Unless you sing the national anthem, or belt out “Sweet Caroline” at Red Sox games, or if you’re that guy who’s had a little too much beer.)

Singing used to be much more common, particularly before radio, television, and the Internet. In the nineteenth century, if you wanted home entertainment, you played and sang music. In an opinion piece written for the New York Times twenty-five years ago, Russell Baker noted that even through World War II, Americans sang more. That was true during the war, when people would even sing in movie theaters to “follow the bouncing ball” tunes. He writes, “The songs may have been silly, melancholy, propagandistic and sentimental, but singing them helped Americans define a communal identity for themselves. Nowadays the absence of singing defines our lack of communal identity, our national apartness, our aloneness.”[1]

But singing together is making a bit of a comeback. Several years ago, I read an article in the New York Times about group-singing, which is when people come together just to sing. They’re not performing or worshiping; they’re not even professionals; they just want to sing with other people. Pete Seeger, the folk singer, was a champion of group-singing. He said, “I think that singing together gives people some kind of a holy feeling. And it can happen whether they’re atheists, or whoever. You feel like, ‘Gee, we’re all together.’”[2] Notice that he is essentially saying that singing together creates community.

Also, research has shown that singing in groups can reduce levels of cortisol, associated with stress and weight gain, and singing can also lower blood pressure. Singing in groups helps produce endorphins and oxytocin, which create feelings of pleasure and fight against feelings of stress and anxiety.[3] So, singing seems to be good for our health.

Here’s another reason to sing: Music is quite simply a good gift. I don’t think that any of us would deny that music is a good thing. Just think of what life would be like if music didn’t exist. We could still function, yet life would be duller. Music is something that we don’t absolutely need, but something that makes life better. From a biblical perspective, we can say that music is grace: An undeserved, good gift from God. James 1:17 says, “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change.”

So, music is a good gift, singing together is good for us, and it creates a sense of community. Those are some good reasons to sing. But there are more.

Within the story of the Bible, God’s people have always sung, particularly in response to God’s great acts of salvation. When God rescued the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt by bringing them through the Red Sea, they sang on the other side (Exod. 15). Moses and the Israelites sang,

“I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously;

the horse and his rider he has thrown into the sea.

The Lord is my strength and my song,

and he has become my salvation;

this is my God, and I will praise him,

my father’s God, and I will exalt him” (Exod. 15:1b–2).[4]

Over four hundred years later, when David was king, the Israelites brought the ark of the covenant into Jerusalem, and David commanded the Levites to identify singers and instrumentalists to “play loudly” and “raise sounds of joy” (1 Chron. 15:16). And then David sang,

8 Oh give thanks to the Lord; call upon his name;

make known his deeds among the peoples!

9 Sing to him, sing praises to him;

tell of all his wondrous works! (1 Chron. 16:8-9)

23 Sing to the Lord, all the earth!

Tell of his salvation from day to day.

24 Declare his glory among the nations,

his marvelous works among all the peoples! (1 Chron. 16:23-24)

When David’s son, Solomon, built the temple in Jerusalem, singers helped the people celebrate (2 Chron. 5:12-13). Clearly, God’s people celebrated important events in their history with singing. They sang of God’s salvation of them and God’s provision for them. And it seems that they didn’t even have to be commanded by God to sing. They sang because they wanted to. They sang because they were thankful for what God had done for them.

And that leads me to another point: We often sing about what we love the most. We praise what we love. That’s why love songs exist. People sing about the one they love. Singing helps us express our greatest desires and our greatest emotions.[5]

I would say that one of the main reasons why we sing is so that we can get theological truths from our heads into our hearts. When we sing, we’re not just rehearsing true statements about God and what he has done. When we sing, we feel what God is like and what he has done for us. God has made us not just to be thinking creatures, but also feeling creatures. And he has given us bodies, so we are supposed to be creatures that not only feel things emotionally, but feel things physically. Singing is a physical act that helps us feel emotionally. When we sing true words about God, we are thinking, feeling, and doing all at the same time.

Sometimes, we sing in response to something we already feel. Sometimes, we sing in order to feel something that we know to be true but don’t yet feel. I don’t know if any of you have sung a hymn to remind yourself of a truth you already know. I know I have. (“It Is Well with My Soul” is particularly good for Christians when they don’t feel that things are well.) I imagine that’s what Paul and Silas did in Acts 16:25 when they were in jail in Philippi. I doubt they sang because they were feeling good. They probably sang to remind themselves of who God is and what he had already done for them and what he promised he would do for them in the future. I think that singing is one of the few things that helps when we’re not feeling thankful to God, when we’re depressed, or when we seem to lost our love for God.

Here’s another reason why singing is good: It helps us memorize truths. How many of us can remember lyrics to the silliest, most worthless songs we heard when we were young? Sometimes, even when we don’t try to memorize words to songs, we do anyway. When we sing hymns and songs that have words directly from the Bible or words based on the Bible, we start to memorize theological truths that stick with us.

Singing is also something that we can do as a congregation. It’s an activity we can all be engaged in at the same time. That’s another reason to sing.

Of course, we also sing because we’re commanded to. In the Old Testament, we find commands to sing, particularly in the Psalms. We read things like:

Sing praises to the Lord, O you his saints,

and give thanks to his holy name (Ps. 30:4).

And:

6 Sing praises to God, sing praises!

Sing praises to our King, sing praises!

7 For God is the King of all the earth;

sing praises with a psalm! (Ps. 47:6–7)[6]

We also find commands to sing in the New Testament, which we’ll look at in a moment.

All of this leads me to a second question: What are we supposed to sing? We have several good reasons to sing, but what does the Bible say about what types of songs we are supposed to sing?

I ask this question because there tends to be tension in churches about whether old hymns or new songs should be sung. What does the Bible actually say about this issue?

There are two passages in the New Testament that tell us what kind of things we should sing. The two passages are parallel; in other words, they basically say the same thing, and they are both written by Paul.

The first one is Ephesians 5:19. To get a sense of the context, I’ll read verses 15–21:

15 Look carefully then how you walk, not as unwise but as wise, 16 making the best use of the time, because the days are evil. 17 Therefore do not be foolish, but understand what the will of the Lord is. 18 And do not get drunk with wine, for that is debauchery, but be filled with the Spirit, 19 addressing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart, 20 giving thanks always and for everything to God the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, 21 submitting to one another out of reverence for Christ.

In this passage, Paul is in the middle of telling the Ephesians how to live in light of the gospel. Paul has spent the first three chapters telling the Ephesians about how God has predestined them for salvation, and how God has redeemed them with Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. He has told them that God the Father has adopted them now that they are united to the Son of God. He has told them that they have the Holy Spirit living inside of them. He has told them that Jesus is above all power and authority on earth. He has told them that they have been reconciled to God and saved from sin and condemnation, all through God’s free gift of grace. They have been made spiritually alive, and this is God’s work. Paul has told them that God has brought them into the one people of God, where the Holy Spirit dwells and where God’s wisdom and glory are displayed.

I take time to describe this because this is the good news of Christianity. We all have turned away from God. We have ignored our purpose for living, which is to have a right relationship with God. Yet God saves his people by sending his Son to live the perfect life that none of us live. He is the perfect representative of God. He is the one who truly worships God always. And yet though he is perfect and never did anything wrong, he was treated as a criminal and he was sentenced to death. He agreed to this plan, dying on the cross in our place, so that everyone who turns to him, trusts him, and follows him has the penalty for their sin paid for. If turning away from God is a crime, we are all guilty. But those who turn to Jesus are declared innocent because Jesus paid did the time for them. He paid their sentence. They are now free to live as children of God.

This is a great reason why we should sing. Christians have been forgiven and have been reconciled to God, not because we are good, but because Jesus is good. And we can look forward to living with God in a perfect world on that day when Jesus returns and makes all things right, when the dead are raised and Christians receive new bodies that cannot die again.

As Paul is telling the Ephesians how to make the best use of their time, he tells them that they shouldn’t get drunk. They shouldn’t be controlled by alcohol. By extension, they shouldn’t be controlled by drugs, either. But they should be controlled by the Holy Spirit. And they should address one another “in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart, giving thanks always and for everything to God the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Don’t miss that: Part of the way that we make good use of our time is by singing to each other.

The parallel passage is in the book of Colossians, which is another one of Paul’s letters. Specifically, the verse is Colossians 3:16, but to get some context, I’ll read verses 12–17:

12 Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience, 13 bearing with one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other; as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. 14 And above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. 15 And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in one body. And be thankful. 16 Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teaching and admonishing one another in all wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God. 17 And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.

Here, you can see that Paul wants us to be more like Jesus. And he wants us to be thankful. But look at verse 16: Paul tells us to “[l]et the word of Christ dwell in [us] richly, teaching and admonishing one another in wisdom, singing psalms and hymns and songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God.” In Ephesians, Paul says to be filled with the Holy Spirit. Here, he says to have Christ’s word dwell in us. If you want to be filled with the Holy Spirit, you need to be filled with Jesus’ words. And, really, the whole Bible is Jesus’ words because Jesus is God. So, if you want to experience more of God, you need his words dwelling in you.

But, as far as music goes, the point in these two passages is that we should sing “psalms and hymns and spiritual songs.” Somehow, this is part of how the Spirit fills us, how the word of Christ dwells in us, and how we teach and admonish each other. What do these three categories of song mean? It seems that “Psalms” are the Psalms of the Old Testament.[7] They are songs of praise. That’s why many Psalms have some musical direction underneath their titles. The words are poetry, and they are like prayers, but they are intended also to be sung. That’s why many churches sing settings of Psalms regularly. The best hymns pull phrases from different parts of the Bible, including the Psalms. And even new songs incorporate ideas and phrases from the Psalms. For example, the refrain “Bless the Lord, O my soul” that we sing in the song “10,000 Reasons” comes from Psalm 103.

A “hymn” here doesn’t refer to a style of music. It refers to a “song of praise.” The word itself is hardly used in the New Testament, but in the Greek translation of the Old Testament, it is used to refer to “songs of praise” or “praise” (Pss. 39:4; 64:2; 99:4; 118:171; Isa. 42:10). This word may refer to the texts we have in the New Testament that appear to be songs, like Mary’s “Magnificat” in Luke 1:46-55, or the “song of Simeon” (the “Nunc Dimittas”) in Luke 2:29-32. Other possible hymns are John 1:1–18; Philippians 2:6–11; Colossians 1:15–20; and 1 Timothy 3:16.

A “spiritual songs” doesn’t mean spirituals, or songs that are “spiritual,” which is pretty vague. It refers to songs prompted by the Holy Spirit. These could be spontaneous songs composed on the spot.

At any rate, these three words refer to types of texts. They do not refer to musical genres. And here’s an important point: We have no idea what the music sung in biblical times sounded like. Modern musical notation started around the year 900, over 800 years after the Bible was completed, and it would take a few hundred years for that notation to resemble what we have today. So we don’t have the sheet music of that time. Obviously, we don’t have any audio recordings of early Christian music. But what Jesus and Paul sang was very different from “Amazing Grace,” and I’m sure even our older hymns might have sounded very foreign to their ears.

The point is that the Bible doesn’t tell us a certain musical style to sing. Musical styles are constantly changing. What’s most important are the words we sing. We need to sing words that reflect and communicate biblical truth. They need to be centered on God. They need to exalt Jesus. And they should be ones that can be understood by people today.

As for music, we should try to sing music that is beautiful, music that reminds us that God is transcendent and glorious. That means we should try to identify some hymns and songs that will stand the test of time. We should also try to sing music that stirs our souls, songs that speak to our hearts. We should sing music that is intelligible to contemporary generations. After all, music is a language unto itself, and we want our language to be understood. That means that some of our songs will be newer, able to speak more directly to the hearts of younger people.

When we sing as a congregation, we want to sing music that can be sung together. That means we can’t sing music that is too difficult to sing. The music we sing shouldn’t have too wide of a range. It shouldn’t be too high or too low. The rhythm can’t be too complex. Handel’s Messiah is a great piece of music, but a church full of average singers won’t be able to sing it well. Our goal is to sing together.

It should go without saying that this emphasis on congregational singing means that our music isn’t meant to be entertainment. We’re not here to put on a show. In fact, the kind of music sung should be one of the least important factors in picking a church. What’s more important is whether the church is preaching the Bible accurately and whether the church is following the Bible’s teachings faithfully.

You may have favorite hymns and songs that we haven’t been singing. And the reason we haven’t been signing them is that they may not be good pieces of music, songs that have a beautiful melody or harmonic progression. They may be pieces that sound like they belong to one particular musical era that has come and gone. Their words may not be theologically sound. That doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy these hymns and songs at home. But for our corporate worship, I try to pick music that is of good theology, good quality, is singable, stirs the soul, and is intelligible to younger generations. That’s a hard balance to achieve.

One last word on the type of music we should sing. The music has to match the text. You can sing the words of “Amazing Grace” to the theme song from “Gilligan’s Island.” In some of the songs we have in our current hymnal, the music doesn’t really fit the text, or even the words don’t fit the theological theme. The greatest example I can think of is “Jesus Is Coming Again” (#567).

Now, very briefly, I want to ask my third question: How do we play music? How do we sing?

We should play musical instruments with excellence. Psalm 33:2–3 says,

2 Give thanks to the Lord with the lyre;

make melody to him with the harp of ten strings!

3 Sing to him a new song;

play skillfully on the strings, with loud shouts.

I think we should all agree that God deserves to be praised with good music that is performed well. Instrumentalists need to play well. Those who lead singing should be able to sing well.

But, at the same time, when we sing together, it’s not a concert. What matters most is our hearts. We need to sing with hearts tuned to praise God. As Jesus said, God is looking for those who will worship him in spirit and in truth (John 4:23). If singing is a part of worship (please don’t confuse singing with worship!), then singing, too, should be done in spirit and in truth.

I also think we should consider singing in parts, in harmony, because when we sing the same song in parts, we are reflecting the body of Christ. But before I get too far with that idea, I want to move to the piano so I can talk a bit more about music. After all, talking about music is like dancing about architecture. (That’s a saying I didn’t make up, though I don’t know where it originated. Also, the original saying, I believe, is “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”) Architecture must be seen and experienced, just as music must be heard and experienced. So, let me move to the piano to demonstrate some points.

As I do that, I want to ask a fourth question: What does music say about God?

Let me continue with the idea of parts. In music, we have the melody, the tune. But we also have harmony, the combination of notes that come together to produce a chord. In music, we can have one chord that consists of many different notes. So, there is unity and plurality in a chord, and there is unity and plurality to a four-part hymn. In the same way, there is unity and plurality to the body of Christ, the church. We are one because we are united to Jesus. But we all play different roles. In that way, the church is like a choir. Not all of us will be soloists. Not all of us will sing the melody, the soprano line. Some will, and they are the more visible members of the church. But some of us will perform supporting roles. We’ll sing the inner voices of the chords, the alto and tenor parts. Some members of the church will play foundational roles. They’ll be our basses. Though we all sing different parts, we’re all singing the same piece of music.

You might even say that the unity and plurality of music echoes the unity and plurality of God. We proclaim that there is one God in three Persons. Now, we can’t say that is exactly like one chord consisting of three notes. Because with God, the fullness of God is found in each Person of God; Jesus isn’t one-third of God. So, the analogy breaks down quickly. But there is perfect harmony in a triad just as there is perfect harmony in the Trinity.

Here’s something else, which may be harder to discuss. I think that music is evidence for the existence of God. If you’re not a musician, this next bit may make your eyes glaze over. In fact, it may make your doughnuts glaze over. It’s that technical.

To illustrate, I want to play a short piece of music on the piano. This is a short piano piece written by the German composer, Robert Schumann (1801–1856). It’s called “Träumerei,” which means “dreaming” or “reverie.” It’s part of a larger collection of piano pieces called Kinderszenen, written in 1838.

Here are the two things I want to point out. In a piece of music like this, the musical language or structure is fairly simple. There are a few main chords that are played, with some secondary chords that provide some color. The music sounds good. It’s harmonious. Mostly, this piece of music contains major triads. It’s written in the key of F major. That’s a diatonic key, consisting of seven notes that alternate between whole steps and half steps. (If you don’t know music, think “Doe, a deer, a female deer; ray, a drop of golden sun . . .”). In that key, there are some very prominent chords, such as F major (F-A-C) and C major (C-E-G) or C7, the dominant seventh (C-E-G-Bb). These chords are very consonant. They sound good together. Even when there are brief bits of dissonance, they resolve. We have a strong sense of where “home” is. It’s F, the tonic. We know that the penultimate chord, C7, must resolve to F and not some other chord, like E major or A-flat major.

Here’s what’s interesting: The fact that all of this sounds so normal and good to us is not because it’s simply the music we’re used to. Some people will say that. We can call them musical relativists. They are the kind of people who refuse to say that any one type of music is better than any other. But I think that’s wrong.

The reason why this music sounds so good, and why other, more experimental music of, say, the twentieth century, sounds bad is because this music is based on mathematical relationships. The relationships between notes in a major or minor key, or between chords in those keys, are based on simple mathematical proportions or ratios.

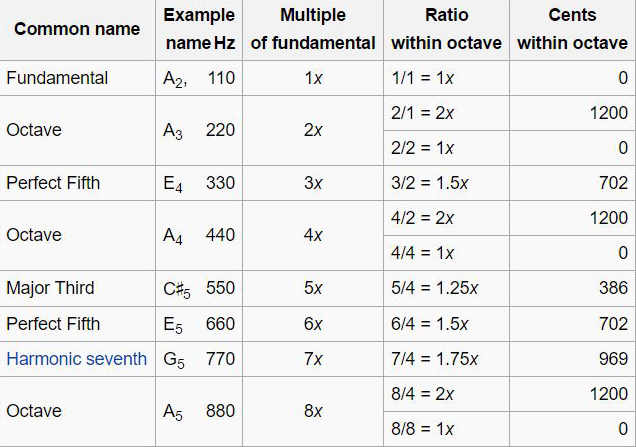

Many of us have heard of “A 440.” That means that the frequency of the A above middle C (A4) is 440 Hz. That means that when I play this key, if it’s tuned to 440hz, the frequency of the strings vibrating will be 440 times per second. The strings will vibrate 440 times per second, which produces sound waves that will oscillate that many times per second. (There will be other vibrations present, which produce harmonics.) Now, if you go to the A above this A (which will be A5), the frequency will be 880. That’s double 440. Every time you go up an octave, the frequency doubles. Of course, every time you go down an octave, the frequency will be divided in two.[8] So, that is a nice mathematical relationship. But you don’t need to know that to know hear the octave.

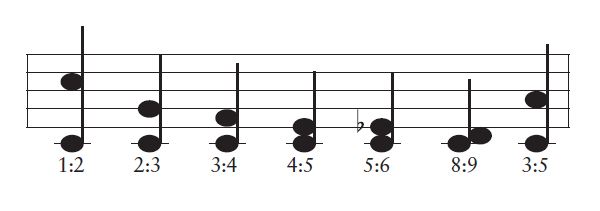

Now, let’s think about the notes within a key. If we’re in A major, the most prominent chord will be an A major triad: A-C#-E (or do-mi-so in solfege). If the A is 440 Hz, the C-sharp should be 550 Hz, and E 660 Hz. That’s a 4:5:6 ratio. The next most prominent chord is the E major chord, the dominant. And that’s based on E, which is 1.5 times the frequency of A. In fact, all of the common intervals are based on simple ratios. The perfect fourth is a 3:4 ratio. The minor third is a 5:6 ratio. The second is an 8:9 ratio. The major sixth is a 3:5 ratio. The minor seventh is a 4:7 ratio. There is obviously a great deal of order to this music. These aren’t complex, seemingly random ratios (like 1:1.719358).

This illustration is found in Vern Poythress’s Redeeming Science.[9]

This table is found on a Wikipedia page concerning music and mathematics.[10]

Here’s the point of all of this: I believe that God created music for our good. I believe he created the language and structure of music based on mathematical proportions. The reason why this music sounds good to our ears is because it lines up with God’s design for music. The combination of frequencies that harmonize mathematically sound good to our ears because God created our ears, our minds, and the building blocks of music. This is not something we created or invented. It’s something that already exists, something that we discovered. And I think that’s true of so much in this world. It’s true of science. It’s true of God’s design for us as human beings. It’s true of God’s design for marriage and the family. When we discover how God has arranged these things in nature, we find harmony. When we go against God’s design, we get dissonance and cacophony. That’s why music that tries to abandon major and minor scales and these basic intervals doesn’t sound right. It’s going against fabric of God’s creation.

Here’s another reason why music is evidence for God. I think this point is easier to understand. Part of what makes music beautiful is that it is bound by the limitations of time. In short, music runs in real time. We can’t stop it. Yes, you can pause on a chord and just hold it. But it has to move onward until the end of the piece. Yes, you can play it again, but the more and more you play one piece of music, the less beautiful it seems to us. There is something elusive about the beauty of music. It’s like the beauty of fall in New England. It’s wonderful to see the leaves turn color. But there’s a short window of time when we can see these beautiful leaves on trees. Before long, the trees are bare and it’s winter. That makes the beauty of this season more precious. Yet here’s also something kind of heartbreaking about it. In this world, we want to hang on to beauty, but we can’t. We want the world to be beautiful always because we have a sense that that is the way the world ought to be. Yet we find that we can’t hang on to beauty because we live in a now-fallen world. So we want beauty, but beauty never lasts, and that fact makes the experience of beauty a bittersweet one. David Skeel calls this the “paradox of beauty.” He writes, “This perception that beauty is real and that it reflects the universe as it is meant to be, but that it is impermament and somehow corrupted, is the paradox of beauty.”[11] The story of Christianity accounts for this paradox. God made a beautiful world that was marred by sin. We now live in a fallen world. We can experience beauty, but it never lasts. We long for a perfect world where beauty remains, where it stays and we don’t get bored of it. And Christianity tells us that Jesus will make this perfect world—and perfectly beautiful—when he comes to restore all things. So even the elusive beauty of music is evidence for the Christian worldview.

One last thing: Music and singing tell us something about God. In one passage in the Old Testament, in the prophet Zephaniah, we’re told that God himself sings over his people. This is Zephaniah 3:14–20:

14 Sing aloud, O daughter of Zion;

shout, O Israel!

Rejoice and exult with all your heart,

O daughter of Jerusalem!

15 The Lord has taken away the judgments against you;

he has cleared away your enemies.

The King of Israel, the Lord, is in your midst;

you shall never again fear evil.

16 On that day it shall be said to Jerusalem:

“Fear not, O Zion;

let not your hands grow weak.

17 The Lord your God is in your midst,

a mighty one who will save;

he will rejoice over you with gladness;

he will quiet you by his love;

he will exult over you with loud singing.

18 I will gather those of you who mourn for the festival,

so that you will no longer suffer reproach.

19 Behold, at that time I will deal

with all your oppressors.

And I will save the lame

and gather the outcast,

and I will change their shame into praise

and renown in all the earth.

20 At that time I will bring you in,

at the time when I gather you together;

for I will make you renowned and praised

among all the peoples of the earth,

when I restore your fortunes

before your eyes,” says the Lord.

The prophet Zephaniah spoke of the day of the Lord (Zeph. 1:7), a day of judgment and a day of salvation. After judgment, God would restore his people, and defeat their enemies. Jesus has taken away the judgment of all who turn to him, trust him, and follow him. Yet we look forward to the day when all of this is completed, when Jesus defeats the last enemy, which is death (1 Cor. 15:26). As we wait for that day, we can know this: God exults over us with loud singing. Earlier, I said that we sing about the things we love. We praise what we love. God sings over his people because he loves them. Let us sing about God, because we love him in return.

Notes

- Russell Baker, “Observer; Hear America Listening,” New York Times, November 2, 1991, http://www.nytimes.com/1991/11/02/opinion/observer-hear-america-listening.html, accessed October 22, 1991. ↑

- Ben Ratliff, “Shared Song, Communal Memory,” New York Times, February 10, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/10/arts/music/10ratli.html, accessed October 22, 2016. ↑

- Stacy Horn, “Singing Changes Your Brain,” Time, August 16, 2013, http://ideas.time.com/2013/08/16/singing-changes-your-brain, accessed October 22, 2016. ↑

- Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are taken from the English Standard Version (ESV). ↑

- See James 5:13b: “Is anyone cheerful? Let him sing praise.” ↑

- See also Pss. 81:1; 95:1; 96:1–2; 98:1, 4–6; 105:2; 135:3; 147:7; 149:1. ↑

- The Greek word, ψαλμος, is used also in 1 Corinthians 14:26, where it may not refer to a Psalm of the Old Testament but to a song of praise or “hymn” (as in the ESV). ↑

- On pianos, the actually frequencies may vary due to something called equal temperament, which makes it possible to play any key and have it sound good. The frequencies I mention here would be found in just temperament, or just intonation, which is a more pure tuning. ↑

- Vern Poythress, Redeeming Science: A God-Centered Approach (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2006), 288. ↑

- “Music and Mathematics,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_and_mathematics, accessed October 22, 2016. ↑

- David Skeel, True Paradox: How Christianity Makes Sense of Our Complex World (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2014), 65. ↑